American Prophets

History textbooks often argue that the United States was founded on the principle of religious freedom, beginning with the Pilgrims who sought refuge from the Church of England. But the America of centuries past was more than a safe haven for religious dissenters. It was also fertile ground for many new religious faiths.

In this hour of BackStory, the Backstory hosts will consider religions that originated or transformed in America, from Christian Science to Scientology. They’ll find out how the threat of colonization briefly united 18th-century Native Americans under a single deity, and how the Nation of Islam found converts among African-Americans in the civil rights era. What makes a religion “American”? Why do so many new faiths sprout from American soil? And what role will 21st century America play in the history of religious innovation?

This episode and related resources are funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this {article, book, exhibition, film, program, database, report, Web resource}, do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

View Full Episode Transcript

PETER: This is BackStory, I’m Peter Onuf. In 1761, an Indian named Neolin called on all tribes to form a new religion with just one god and one purpose, expelling the British. And it almost worked.

ADAM JORTNER: The British government is absolutely willing to say Neolin’s religion has won this war.

PETER: As the land of opportunity, America has been fertile ground for new religions and their founders. Today on BackStory, we’ll explore the stories behind these American prophets. We’ll look at the Mormon migration to the west and the popularity of the Nation of Islam in prisons. We’ll also ask what they reveal about America.

ZAHEER ALI: They seem at first to be very exotic and strange, but the closer you look at them, the more they hold up a mirror to ourselves.

PETER: Coming up on BackStory, American-born religions.

MALE SPEAKER: Major funding for BackStory is provided by an anonymous donor, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, and the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

ED: From the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, this is BackStory with the American Backstory hosts.

BRIAN: Welcome to the show. I’m Brian Balogh, and I’m here with Peter Onuf.

PETER: Hey Brian.

BRIAN: Ed Ayers is away this week.

We’re going to start off today in Los Angeles in 1906. Here’s the scene, an African American preacher named William Seymour stood before a crowd of worshippers in an empty warehouse. The dilapidated buildings sat on a rundown strip called Azusa Street, and had recently housed livestock.

ESTRELDA ALEXANDER: So there was sawdust on the floor, there were no seats, the altar was makeshift orange crates—two or three of them sat on top of each other.

BRIAN: This is author Estrelda Alexander. She says no congregation in America resembled Seymour’s. First off, the soft-spoken preacher wasn’t in charge. Instead, the congregants directed the action in a raucous cacophony of song and dance. They beat washboards and tambourines. They even became possessed by the Holy Spirit.

ESTRELDA ALEXANDER: There was a lot of loud praising—hallelujah, thank you Jesus, whatever came to people’s minds. There was also outbursts of speaking in tongues—that happened regularly—and there was also outbursts of prophetic messages. So it was loud, it was so loud that often the neighbors called the police.

BRIAN: This was a new form of Christian worship, now known as Pentecostalism. Seymour’s church was also unique because of who came to worship. African Americans, white Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, and immigrants from China, Japan, and Europe—they all flocked to the storefront church.

ESTRELDA ALEXANDER: People of different races actually embracing, and touching, and singing and dancing with each other.

BRIAN: Between 1906 and 1909, tens of thousands of people joined the Azusa Street Revival. At its peak, services were held around the clock, seven days a week. Los Angeles even earned the nickname the American Jerusalem.

But many Americans looked at this new form of worship with contempt. A 1906 LA Times article described the congregation as a quasi-cult, warning its readers of a new sect of fanatics breaking loose.

MALE SPEAKER: Night is made hideous in the neighborhood by the howlings of the worshippers, who spend hours swaying forth and back in a nerve-wracking attitude of prayer and supplication. They claim to have the gift of tongues, and be able to understand the babble.

BRIAN: Other Americans were offended by Azusa Street’s embrace of integration. At the time, racial segregation was the custom, if not the law of the land. But Alexander says that racial inclusiveness is exactly what attracted all kinds of people to Azusa Street, and they found empowerment in the church’s message that everyone—no matter how humble or broken—has direct access to the Holy Spirit. The prophecies, the miracles, the speaking in tongues—well, that was the proof.

ESTRELDA ALEXANDER: You’re a lowly farmer, you’re a lowly drug story clerk, but you come into a movement where you are able to invoke the name of God to bring about divine healing. Or somebody comes into the meeting and they are an alcoholic, and they come to the altar and they are prayed for, and they get up and they walk away from alcoholism. And this sense of empowerment is not just an emotional high, but it’s life changing.

BRIAN: By the 1920s, the Azusa Street revival largely fizzled, but the raucous spirit of the Pentecostal movement quickly spread through the South, Midwest, and eventually worldwide. Missionaries from Azusa Street tried to maintain racially-mixed services, but once they moved outside LA, that was dangerous. So the movement split into mostly separate black and white denominations.

PETER: Nevertheless, Pentecostalism is the fastest growing branch of Christianity today, with nearly 300 million followers worldwide. And Estrelda Alexander says that there’s a reason that this religious movement first took off in the American West, a land where people were searching for a fresh start.

ESTRELDA ALEXANDER: What made the difference in America, I think, is the openness. This was a pioneer country. Even in 1900, we were still pioneers, we were still open to testing and trying new things.

PETER: Those are just a few of the factors that have made the United States such fertile soil for new religions and expressions of faith.

BRIAN: Today, we’ll be exploring some of those American religions, and the charismatic figures who built them, from Mary Baker Eddy and the origins of Christian Science, to Brigham Young and the Mormon settlement of Utah. We’ll also look at way the Church of Scientology was shaped by the hunt for Cold War communists.

PETER: But first, let’s back up and look at the birth of a new religion before the American Revolution. In the 18th century, Native Americans living in Appalachia prayed to a wide assortment of spirits. They were called Manitou.

ADAM JORTNER: And there are spirits for all kinds of forces and beings. There’s a spirit of thunder, there is a spirit of the bear, all the way down to a spirit of the strawberry.

PETER: This is Adam Jortner, a historian at Auburn University. Jortner describes this native religious tradition as a spiritual marketplace.

ADAM JORTNER: They’re always bartering with different spirits and trying to get different goods and booms from them, and individual Native Americans or Native American groups might venerate different Manitous.

PETER: Those beliefs baffled Christian colonists who got their spirituality from a very different kind of marketplace.

ADAM JORTNER: Monotheism is like a Walmart, you go to one God to get everything.

PETER: Now Natives also believed in a supreme god, a so-called Master of Life. But unlike the Christian God, the Master of Life created the universe and then left it alone.

ADAM JORTNER: But there’s a problem, and that is—of course—that the disease is ripping through Native American communities, and as we get into the 18th century, there’s pressure from white communities that are expanding westward and they’re taking Native American land. You’re still praying to Manitou, you’re still making sacrifices as you normally would, but you aren’t getting the benefits. This is a spiritual crisis as well as a political crisis, your religion isn’t working anymore.

PETER: While Natives desperately searched for help, a divine solution presented itself to a Delaware Indian named Neolin.

ADAM JORTNER: Neolin, we know almost nothing about where he came from and we know almost nothing about what happened to him. But from 1761 to 1766, he transforms Indian life west of the Appalachians.

One night while he was cooking dinner, he saw three paths just appear before him, and he got the feeling that he needed to walk down these paths. And two of those paths led to fire, and one of those paths—the most difficult path—he walks along and he encounters a sheer mountain wall. And he is informed that he needs to climb this wall using only his left hand and his left foot.

And he climbs up, and at the top of this mountain there is a celestial city, and that is where he meets the Master of Life. And the Master of Life informs him about the changes that need to happen. They need to institute worship of the Master of Life, they need to give up alcohol.

They need to reject national designations. There shouldn’t be anymore Ottawas or Ojibwes or Iroquois. These designations need to go away and everyone needs to be one group of Native Americans, the favored people of God. And if they do this, they can expel the British from their lands.

PETER: So Adam, this trip that he takes—from that journey, he returns with the news. And of course, that news is both spiritual but it’s also profoundly political, isn’t it?

ADAM JORTNER: I think so, it’s both. Once his message gets out there, once people start hearing about it—Native American groups start hearing about it—the British become very wary of all this preaching. And probably Neolin’s greatest convert is Pontiac, who is a Ottawa chieftain who accepts this idea and says, yes. And of course it’s Pontiac—with this preaching behind him—who begins to organize the tribes west of the Appalachians into a fighting force that expels the British from most of their forts, from most of their military positions.

PETER: OK, tell us a little bit about the lay of the land, Adam, that sets the stage for what’s now known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. He has specific targets, he wants to get rid of the British. What’s the big picture here?

ADAM JORTNER: I mean, the big picture is that once Britain defeats France in the French and Indian War, there’s a huge chunk of territory in what is today Ohio, Pennsylvania, the Midwest that Britain takes control of but has never conquered militarily. They just occupy the French forts that are already there. Pontiac’s goal is to attack every single fort to expel the British, and in that way force them out of the country.

And they do just that, and I think there’s all but three forts that are conquered. And actually at Michilimackinac, they conquer the fort by—they’re having a lacrosse game outside, someone throws the ball into the fort, and then they run in to chase after the ball and then once they’re in, take over. And they’re successful enough that the British actually cave and they say, this is not worth the blood and treasure it would take to conquer this land.

The British set up a Proclamation line in 1763, they actually forbid white settlement west of the Appalachians. So the British government is absolutely willing to say, you guys have won. Neolin’s religion has won this war.

PETER: So talk a little bit, Adam, if you would, about the aftermath. Neolin’s message remains powerful in Indian country, and you might say it’s partly responsible for the tremendous resistance that’s put up to westward expansion over the next half century.

ADAM JORTNER: Yeah, I think that’s right. Pontiac’s Rebellion is eventually rolled back. By 1768, there are already breaks in the Proclamation line and white settlers are coming across, but guns can’t stop an idea. Yeah, you can stop a military rebellion, but those religious ideas are deep-seated and they move around and that is not something that an army is well-equipped to take care of.

Neolin’s ideas are going to take other forms in the next 50 years. There’ll be other prophets among other Native American groups who preach similar messages, who also take journeys along forked paths, who also meet the Master of Life, who also preach about abstaining from alcohol, rejecting white culture. And these are people like the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa, who emerges in Indiana in the 1800s, or Handsome Lake, the Seneca prophet who emerges in upstate New York in 1799. And Kennekuk, the Kickapoo prophet who emerges in 1819.

These prophets all preach resistance to white encroachments, and they preach a religious message of divesting themselves of white culture and going back to the worship of the one god of Indians, the Master of Life. But like every new religion, it is not universally accepted. There are Native American people and Native American groups that reject this message, that say no, our traditional religions are correct. And in fact, it’s these Nativists—it’s these new ideas from Neolin and Tenskwatawa and Handsome Lake—these are wrong, these are causing our problems.

So it also creates conflict within the Native American communities, as well, which explains in part why these—ultimately, you never get a situation where all Native Americans band together to fight white encroachment.

PETER: But one of things we’re trying to do on this show is talk about what it is about the American setting—about the world that Indians and Europeans both inhabit—that might be distinctive. Does Neolin’s teaching—and do the Nativist religions that follow in his wake—do they seem somehow to you distinctively American? Would you argue that there’s something that they have in common with their counterparts across the cultural frontier?

ADAM JORTNER: One of the things that makes Neolin’s religion so distinctively American is movement. One thing that’s true about the frontier and about Americans generally is they’re always moving around, and that happens among Native American communities first. That the Delawares have been ejected from their lands on the east coast and they’ve traveled, and now they live in Ohio, and there’s been all kinds of movements in Indian country in the Seven Years War. These are the communities that Neolin preaches to.

And that’s very true, I think, of American religions generally, that new American religions tend to grow out up on the frontier. Many new religious come out of Los Angeles, which is a city of people who have moved to a new place. I think Neolin’s religion is—in many ways—the first religion to really take advantage of the fact that people are all moving around and they’re ready to hear a new message.

PETER: Adam Jortner is a historian at Auburn University and author of The Gods of Prophetstown. Earlier, we heard from Estrelda Alexander. She’s the President of William Seymour College in Bowie, Maryland, and the author of Black Fire: One Hundred Years of African American Pentecostalism.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BRIAN: Now it’s safe to say that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints is a true American success story. The exact number of adherents is contested, but according to a recent Pew Research Center survey, there are nearly 4 million adult Mormons in America.

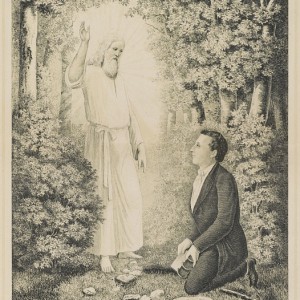

PETER: Those numbers would have been hard to imagine back in 1844. Hundreds of Mormon converts had been killed or attacked as they attempted to build settlements in Missouri and Illinois. An angry mob had just murdered the church’s founder and prophet, Joseph Smith, in Carthage, Illinois. The Church was in turmoil.

JOHN TURNER: And it wasn’t clear who should take charge after his death.

PETER: That’s scholar John Turner. He says that following Smith’s death, rival leaders split the church. Some Mormons headed east to Pennsylvania, some north to Michigan, but most followed a forceful Mormon convert named Brigham Young out west to a part of Mexico called Utah.

BRIAN: Young’s decision to trek to Utah would have a tremendous impact on his struggling church, and on the American West as a whole. We’re going to take a moment to explore how this mass migration transformed Mormonism and almost caused a shooting war between these new settlers and the US government. Young’s colony grew very quickly once word spread that he’d founded the New Zion.

JOHN TURNER: There were thousands of Latter Day Saints who reached what became the Utah territory each year from the late 1840s through the 1860s, many of them coming from as far away as England.

BRIAN: But the Mormons weren’t the only ones interested in the territory. The US government soon claimed Utah and appointed Brigham Young governor. He oversaw not just present-day Utah, but most of Nevada, along with parts of Colorado and Wyoming. That made him the head of the church and state for an area the size of France.

Young saw an opportunity to create a new form of government, a theo-democracy.

JOHN TURNER: I think it was probably a little bit more theo than democracy, at least at first. The most simple way of understanding it is that those who ran for those local and territorial offices essentially needed Brigham Young’s approval to do so.

BRIAN: So he was a political boss of sorts?

JOHN TURNER: He was the political boss, absolutely.

BRIAN: But to Young, this meant more than just Mormons holding political office, it also meant that Saints were finally safe to publicly embrace one of the church’s most controversial teachings, polygamy. The rest of the country didn’t think much of Mormon marital practices. Politicians called polygamy a relic of barbarism that should be stamped out alongside slavery. And in 1857, President James Buchanan tried to put an end to Young’s experiment in theo-democracy once and for all.

JOHN TURNER: Buchanan decided to appoint a new governor. And he knew that this would create controversy and that it would meet opposition, and so he sent a substantial expedition of US Army troops to accompany that new governor.

BRIAN: By substantial, Turner means a fifth of the entire US Army.

PETER: But Brigham Young refused to back down.

JOHN TURNER: He gave what you could really call wartime sermons, he mobilized Utah’s militia. He sent that militia to obstruct the approach of the Army into Utah.

PETER: One militia leader ordered his men to obstruct the US troops by every means possible.

MALE SPEAKER: Use every exertion to stampede their animals and set fire to their trains. Burn the whole country before them and on their flanks. Keep them from sleeping by night surprises. Blockade the road by felling trees or destroying the river fords where you can. Leave no grasp before them that can be burned.

PETER: Young’s orders were to harass, rather than engage, US troops directly. The Utah militia never actually faced the US Army in battle, but as Turner reminds us, there were civilian casualties. Mormon militia killed more than 100 members of an American wagon train passing through southern Utah in what came to be known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

BRIAN: Why were the Mormons so belligerent? After all, Buchanan had every right to appoint a governor of the Utah territory. But Turner says that’s not how Young and his followers saw it.

JOHN TURNER: Any time they had settled anywhere else, there had always been trouble, and mobs and state militias had harassed them and driven them out. And I think Brigham Young could very persuasively tell his people look, this is what happened in Missouri and Illinois, it’s going to happen again. And we either fight or we let them come persecute us.

BRIAN: The Utah militia tactics, combined with a tough winter, prevented US troops from reaching Salt Lake City for months.

JOHN TURNER: And Brigham Young ultimately decided not to fight. I think Young recognized it was a fight he wasn’t going to win, and so he accepted the presence of this non-Mormon governor.

BRIAN: In the short term, Brigham Young came at a head. The new governor often sided with Mormons against the federal government, and Young still had a lot of political clout. He remained the leader of the church until his death in 1877.

JOHN TURNER: In the long term, it was a big step toward establishing national sovereignty over the territory. And so by the 1870s, there are successful prosecutions of Mormons for polygamy. So in the long run, the national government asserted its political sovereignty over Utah.

PETER: By the 1890s, it was clear that Young’s dream of a Mormon theo-democracy in the west would not survive. Church leaders, under intense pressure from the federal government, publicly abandoned the practice of polygamy. Secular officials were in charge of the territory. But Turner says that while Young failed to establish a Mormon kingdom, his decision to settle Utah forged something far more enduring.

JOHN TURNER: It turns the church into a people with a shared history, a shared place. In many ways, I think that developed that strong Mormon ethic of cooperation and self-sufficiency that is still very characteristic of the church.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

PETER: John Turner is a professor of Religious Studies at George Mason University, and author of Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BRIAN: In recent decades, one American-born religion has stirred up a lot of controversy for its rejection of modern medicine, that’s Christian Science. In 1990, followers David and Ginger Twitchell were convicted of involuntary manslaughter after their infant son died from an obstructed intestine. The parents had turned to prayer as treatment.

The ruling was later overturned, but the high profile case—as well as other children’s deaths—brought a lot of negative attention to the church. In recent years, Christian Science leaders have sought to modify church practices in the face of falling membership.

PETER: That’s the story today, but BackStory producer Nina Earnest wondered if this American religion’s early history might help explain its controversial teachings. Here’s Nina with the story.

NINA EARNEST: In 1866, Mary Baker Eddy slipped on the ice in Lynn, Massachusetts. A doctor told her that the injuries to her head and neck were life-threatening. Everyone around her feared the worst, but then Eddy—

DAVID HOLLAND: —called for the Bible and read an account of Jesus healing in the New Testament, and had an epiphany—

NINA EARNEST: This is religious scholar David Holland, who is working on a biography of Eddy.

DAVID HOLLAND: —that the power to heal was the power of truth and if she simply believed in truth, that this injury that she had encountered would not hold her down.

NINA EARNEST: And it didn’t. At that moment, Holland says, Eddy felt freed from her pain and suffering. She would later describe it this way.

FEMALE SPEAKER: The result was that I arose, dressed myself, and ever after was in better health than I had before enjoyed. That short experience included a glimpse of that great fact that I have since tried to make plain to others, namely life in and of spirit—this life being the sole reality of existence.

NINA EARNEST: Mary Baker Eddy had struggled with sickness throughout her life, including digestive troubles, back pain, and respiratory infections. But following the fall at Lynn—as believers call it—Eddy made it her mission to spread her own gospel. Her new philosophy looked to the Bible to emphasize Jesus’s healing practices, and by 1879 she and her disciples had officially founded a new church and a new belief system, the Church of Christ, Scientist.

DAVID HOLLAND: Christian Science is essentially the belief that matter is not real, and everything that you can draw from that central fact is entailed in that central belief.

NINA EARNEST: If matter is not real, then the body is not real. If the body is not real, then terrible things that affect the body aren’t real either, such as death and disease.

DAVID HOLLAND: She offered the promise that through prayer and correct principles, people could be liberated from the tyranny of the physical body and find true, lasting, permanent health.

NINA EARNEST: And even though Mary Baker Eddy did allow her followers to receive some medical attention, the goal was to use less and less as their spirituality deepened.

DAVID HOLLAND: And I think within the culture of Christian Science, to have to appeal to medicine carries a certain stigma.

NINA EARNEST: In the late 19th century, Americans really took to Mary Baker Eddy’s ideas. There were more than 1,000 Christian Science congregations by the time Eddy died in 1910, though exact membership numbers are hard to come by. Titanic figures like William Randolph Hearst and Mark Twain weighed in on its popularity, Hearst to support Eddy and Twain to accuse her of being a for profit prophet.

Twain might’ve thought that supporting Eddy was irrational, but there are many reasons her teachings spoke to Americans. For one thing, 19th century physicians weren’t exactly models of professionalism. Doctors regularly administered mercury and morphine for vague illnesses like hysteria. Women in particular were targets of these treatments. Let’s just say that the medical profession was a field in transition.

DAVID HOLLAND: We might think of it as a moment in which a rising, scientific, professionalized medical community had begun to debunk previous folk practices, but had yet to really achieve a high level of respectability or the confidence of Americans generally. And in that vacancy, movements like Christian Science proved incredibly attractive.

NINA EARNEST: And on top of that, Christian Science put power back in the hands of its practitioners—in one group, in particular.

DAVID HOLLAND: Christian Science was particularly popular among middle class women.

NINA EARNEST: Mary Baker Eddy is one of few American women to found a religion, and that’s reflected in her theology. God was referred to as Mother Father God. If bodies didn’t exist, then gender didn’t matter. For many women, the fact that Christian Science—for the most part—shunned the growing medical profession may have been part of the appeal.

DAVID HOLLAND: With the professionalization of medicine, folk healing practices that had traditionally been the domain of women were increasingly moving into the hands of men to the exclusion of women. Christian Science returned a healing power to women, and so religious authority—which is based on the capacity to heal—is not gendered specifically, but in fact transcends gender.

NINA EARNEST: Christian Science membership began to drop in the second half of the 20th century. But in her time, Mary Baker Eddy offered American believers something empowering. We’re not saying it was granted, but she offered at least the promise of freedom from their own bodies.

BRIAN: Nina Earnest is one of our producers. David Holland helped tell that story. He’s a professor at Harvard Divinity School. He’s writing a comparative biography of Mary Baker Eddy, and Seventh Day Adventist leader Ellen White.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BRIAN: We’re going to turn now to a movement that you might be familiar with from newspaper headlines, not history books. The Church of Scientology.

PETER: Scientology has attracted Hollywood celebrities like Tom Cruise and John Travolta. Several high-profile defectors and an HBO documentary alleging systematic abuse of church members have also garnered attention in recent years. But religious scholar Hugh Urban says that the tabloid version of Scientology often misses a key fact about the religion. It is, in many ways, a product of the Cold War.

HUGH URBAN: It emerges in the years after World War II and it really reflects the combined sense of tremendous optimism, hope, excitement, energy, but the same time there’s also the underlying fear in the 1950s of nuclear war, of Communism.

PETER: More on that in a moment, but first some background. Scientology’s founder, L Ron Hubbard, made his name as a science fiction writer. Then in 1950, he penned a wildly popular self-help book called Dianetics. Hubbard claimed that he could teach readers how to control their own minds and erase negative memories, and many gave it a try.

HUGH URBAN: There are little Dianetics clubs that spread all over the United States and England, and it was really a fad that caught on like wildfire. But it was also a decentralized movement, and so the revenue wasn’t always coming back to Hubbard.

PETER: Then the movement fizzled, but Hubbard used it as a springboard to create the Church of Scientology. Urban says Hubbard had two reasons for transforming his self-help movement into a religion.

HUGH URBAN: First, Hubbard said that people practicing Dianetics began to remember past lives. And this led him to the belief in an immortal self or spirit or soul, what he came to call the thetan. So that’s one element.

A second is that the FDA began to investigate Dianetics, and so Hubbard realized that if he turned in the religious direction—what he calls at one point the religion angle—then the FDA couldn’t go after him because he wasn’t making claims about physical healing any longer, but was making claim about spiritual healings.

PETER: And that’s really the interesting story that you’re telling, a very savvy move, as you’re suggesting. If we did something so vulgar as refer to a business plan, that was a terrific one.

HUGH URBAN: Well, I don’t think it is vulgar because Hubbard was pretty clear that A, this is a church but also, it has a business component. And he wrote a lot about the business side of things because the higher levels of training or auditing in Scientology become quite expensive.

So basically, they have what’s called the Bridge to Total Freedom, which is a hierarchical road map of the Scientology path. And it begins with the lower level Dianetics training until you get to the state that’s called Clear—when you’ve cleared the negative experiences from this particular lifetime. The estimates that I’ve seen is that to get to level OT VII—the last one that Hubbard finished before his death—would run between $300,000 and $400,000.

PETER: So we think of Scientology as an outlier, as a strange cult—which is what it has frequently been described as. But you argue that it’s actually very American in its history and in its teachings. Maybe you could explain that?

HUGH URBAN: Sure. I would say it’s very American for several reasons. The way in which it picks and chooses and synthesizes components from many, many different traditions, and Hubbard himself was quite upfront about that. He says when he wrote Dianetics that he tried everything—he tried every form of psychoanalysis, he explored every religious option, explored medicine—and basically he came up with this remarkable synthesis.

Then the other thing I would argue is uniquely American about Scientology is the combined sense of optimism that characterizes both Scientology and American life in the years after World War II, but also the sense of unease surrounding the Cold War and Communism. Hubbard himself presented Dianetics and Scientology both as the ultimate solutions to nuclear war. He saw human beings as on the brink of destroying themselves with nuclear weapons, and what we need now, he argued, is for humans to be able to control themselves, control their own minds.

He was also preoccupied with Communism. He wrote multiple letters to J Edgar Hoover in the FBI, identifying Communist threats around him. And then, I would say, the secrecy components that you see throughout Scientology’s history is really a mirror image—in many ways—of the larger concerns with secrecy, information control, surveillance.

Scientology developed its own intelligence bureau called the Guardian’s Office in the mid 1970s when Scientologists infiltrated IRS offices, one of the largest infiltrations in US history that then led the FBI to launch the largest raid in the bureau’s history on Scientology offices. So there’s this funny interplay between Scientology and agencies like the FBI.

PETER: Was the engagement of government and the Church of Scientology an important episode in church-state relations in America? Do you people in religion departments consider it so?

HUGH URBAN: I do. So the 1950s and 1960s was a time of tremendous religious experimentation in the United States. You had new forms of Hinduism and Buddhism, and then you had all these new religions popping up. So it was a time when the very definition and understanding of what religion is was being called into question as we went from a society that just had Protestant, Catholic, Jew, to a society where there’s Hare Krishna, Zen Buddhists, and Raelians and everything else.

And also, I think how government agencies dealt with religion was also changing during that period—particularly controversial new religions. Courts and law enforcement agencies have typically had a very hands-off attitude towards religions because we value religious freedom so much. But at the same time, we have tax exemption for religious and charitable groups which means that, ironically, it has fallen by default to the IRS to make many of those calls about what is and isn’t a religion.

Initially, Scientology had little trouble getting tax exemption in the United States in the 1950s. Then the IRS begin scrutinizing them more closely and determined that most of the revenue was going to Hubbard and his family, and so stripped Scientology of its exemption in the 1960s. And that led to this massive 25-year war between Scientology and the IRS that involved literally thousands of lawsuits.

And then in 1993, Scientology reached a settlement with the IRS where Scientology paid $12.5 million, and then got fairly remarkable blanket exemption from the IRS that covered not only Scientology churches and the religious side of Scientology, but also exempted things that are quite secular like Galaxy Press, which publishes Hubbard’s science fiction.

PETER: So we like to think—in our classic narrative of American history—that church-state relations were resolved by freedom of religion. We go back to Jefferson, but you suggested it’s actually a work in progress and the future is uncertain.

HUGH URBAN: Yeah, I think it’s always a work in progress. And that’s one of the things that has drawn me to the study of new religions, is that they have consistently, repeatedly challenged the way we think about religion and what we understand to be religion. How we draw the boundary between religion and business, for example, in the Church of Scientology. And Scientology is just one example of that ongoing rethinking of religion.

PETER: Hugh Urban is a professor at the Ohio State University, and the author of The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BRIAN: We’re going to turn now to a religion that didn’t grow out of older forms of Christianity, like Pentecostalism, Mormonism, or Christian Science.

PETER: In 1934, Elijah Muhammad took over the Nation of Islam from its founder, WD Fard. This new religious movement drew its practices from traditional Sunni Islam—belief in Allah, prayer five times a day, fasting during Ramadan, mandatory charity, and pilgrimage to Mecca. The Nation of Islam grew throughout the 1930s and ’40s, attracting African American migrants from the South with its messages of black empowerment, self-reliance, and moral reform, all embedded in those Muslim rituals and practices.

ZAHEER ALI: That’s the origin story of the Nation of Islam in about maybe 10 tweets.

PETER: This is Zaheer Ali. He’s writing a doctoral thesis about the Nation of Islam in Harlem, at Columbia University.

BRIAN: Now if Americans know anything about the Nation of Islam, they’re probably most familiar with Malcolm X and his famous jailhouse conversion. In fact, prisons were a hotbed for recruitment in the 1950s and ’60s, partly—says Ali—because its Muslim tenets gave prisoners lives a spiritual structure.

ZAHEER ALI: And this is true, of course, in Islam. The five daily prayers, the fasting, the dietary restrictions, the moral restrictions with regard to sexual relationships.

BRIAN: So are you saying that regimentation fit well in an environment that obviously was hyper-regimented, a prison?

ZAHEER ALI: I do, and I think what it does is it gives that regimentation a different meaning, right?

BRIAN: Right, it’s turning it to one’s own purposes.

ZAHEER ALI: Exactly. The Nation of Islam effectively created black spaces in places that had been designated for black people. So where you see a prison cell, I see a Mosque. Where you see a ghetto, I see a community.

BRIAN: The Nation’s popularity in prisons wasn’t an accident. Ali says the attributes that made the religion catch on behind bars were central to the faith from the very beginning.

ZAHEER ALI: At the core of the Nation of Islam has always been a focus on black agency, the idea that black people were original, were first, at the center of the story. Write their own story, tell their own story, build their own schools, their own homes, their own businesses. Primordial blackness is at the heart of the Nation of Islam.

BRIAN: And what was it about the United States in the early 1930s that would’ve provided a catalyst for that kind of thinking?

ZAHEER ALI: Well, one of the things in thinking about the emergence of the Nation of Islam is to think about this emergence of new religious movements during the Great Migration era in the 1910s and ’20s leading into the Great Depression. Where you have people coming from the South—mostly from a Christian background—and finding in the North not always feeling welcome in the established churches, and so people began to set up storefront churches.

And certainly the Nation of Islam comes out of this milieu, but then hand this is genesis story that no one had heard before. The white race was a genetically engineered group of people whose purpose was to bring misery to black life.

BRIAN: Sounds like the kind of thing that would be banned today under genetic modification.

ZAHEER ALI: It is, but you know what’s interesting is that during the 1920s and ’30s, American scientists were leading the ideas of eugenics, right? And so when people heard Elijah Muhammad’s story of this scientist who engineered a white race, what they heard was the inverse of what scientists were saying at the time, and what they heard was something that put black people at the top.

But the community didn’t just sit around and talk about white people beyond that. There was a strong focus on what black people could do to change their own condition. There is this verse that was very popular, “God will not change a condition of a people until they change themselves.”

And so this focus on self-reliance in the form of establishing businesses, establishing their own network of schools—within the context of American racism and Jim Crow segregation in the South and the way segregation had played out in the North—that within that context, that black people could actually construct and establish their own communities that were thriving.

BRIAN: Any why Islam?

ZAHEER ALI: So part of the appeal to African Americans with Islam is this appeal of historical recovery. We know that those enslaved people who were brought from Africa came from predominantly Muslim parts of West Africa. That doesn’t mean they were all Muslim, but certainly a significant portion of them were Muslim. And so there was this appeal to the religion of your ancestors.

BRIAN: If I’m not mistaken, the ’50s and ’60s were a tremendous period of growth for the Nation of Islam. What do you attribute that to?

ZAHEER ALI: Certainly a movement that declares the white man as the devil is assisted greatly when people turn on the television and see black children getting hosed down in Alabama, or dogs being sicked on them, or reading about the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church.

BRIAN: So some of the same catalysts as for the Civil Rights Movement.

ZAHEER ALI: Yeah. Yeah, where maybe some people said oh my God, how horrible, you had people who had accepted the beliefs of the Nation of Islam saying to themselves, we told you. For them, this was a confirmation of how violent white supremacy had become towards black lives.

And so they argued, why would you want—the integrationists to the desegregation—why would you fight to eat from a restaurant that didn’t want to serve you in the first place? Why would you even trust those people’s food, right? Why not you have your own restaurant? The Nation of Islam’s ideas of cooperative economics, of developing black-owned businesses, these were ideas that were very popular.

BRIAN: Here’s a show on American-born religions, and you and I have talked a lot about politics in spite of that. Tell me what we might miss by conflating politics with religion when we talk about the Nation of Islam, or is that the whole point of the Nation of Islam?

ZAHEER ALI: No, I’m really glad you asked that question because there is much of the Nation of Islam that speaks to the political condition of black people in America, but that alone would not sustain a spiritual community. And so it’s important to think about how the Nation of Islam provided spiritual alternatives for its members. I’ll give an example, we’re in December. During much of the Nation of Islam’s history, it practiced the Muslim holy ritual of Ramadan in December.

Elijah Muhammad really skillfully prescribed Ramadan for his followers in December for several reasons. One, to move his community out of celebrating Christmas, so I think he understood the need for spiritual alternatives for his community. And certainly internal to this community were people who were searching for a way to connect to a higher power, for a way to connect with each other, and the rituals that helped make that happen.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BRIAN: Zaheer Ali is a doctoral student at Columbia University, and oral historian at the Brooklyn Historical Society.

Peter, earlier in the show we heard this phrase, the spiritual marketplace. And it strikes me that, that phrase might be applied to virtually all the religions that we’ve talked about today.

PETER: Yeah, I think that’s true, Brian, and it’s partly because of the separation of church and state. There is no state religion and that’s an optimal circumstance for new forms of worship to flourish.

But I think it’s important to emphasize that though there is this great range of religious expression, that every new religion has faced enormous challenges because the larger society often finds these new forms of religious faith and expression to be threatening and dangerous. It’s not just that you’re free to worship the way you want, but if you do want to worship that way you’re going to pay a price for it.

BRIAN: Peter, to what extent has that persecution, in fact, been key to creating enduring communities?

PETER: I think it’s absolutely central. I mean, you could say that all national histories are histories of persecution. And so in some ways, a faith community is like a little nation that’s within the larger nation, as in the Nation of Islam. A faith community that is aspiring to connect with their god—in a way, they transcend the idea of nation but they reflect the idea of nation.

BRIAN: And yet, once they are established, they seem—in many of the cases we’ve talked about, all of them, really—to endure, sometimes even thrive, in circumstances completely different. And that simply speaks to me about the human quest for the spiritual that we simply can’t reduce to specific place, time, and historical facts. Really, the tools of our trade, Peter.

PETER: I think that’s so right, Brian. That’s the great paradox of studying religion. We want to put them in neat little boxes so that we can explain them, when in fact what we have is fellow Americans, fellow human beings engaging in the most important effort.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

PETER: That’s going to do it for us today. But if the spirit moves you, head over to our website to let us know what you thought of today’s episode. While you’re there, ask us questions about our upcoming shows. We’re working on one about the history of passing in America and another about the American tradition of trial watching.

You’ll find it all at backstoryradio.org, or send an email to backstory@virginia.edu. We’re also on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter @BackStoryRadio. Whatever you do, don’t be a stranger.

BRIAN: BackStory is produced by Andrew Parsons, Brigid McCarthy, Nina Earnest, Kelly Jones, and Emily Gadek. Jamal Milner is our engineer, Juliana Daugherty is our digital editor, and Melissa Gismondi helps with research.

Special thanks this week to Kathleen Flake, Jeffrey Ogbar, Matt Headstrom, and Jamilah Karim. And thanks to our readers, Greg O’Malley and Sarah McConnell.

PETER: BackStory is produced at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities in Charlottesville. Major support is provided by an anonymous donor, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, and the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Additional funding is provided by the Tomato Fund, cultivating fresh ideas in the arts, the humanities, and the environment. And by the History Channel, history made every day.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Brian Balogh is Professor of History at the University of Virginia. Peter Onuf is Professor of History Emeritus at UVA and Senior Research Fellow at Monticello. Ed Ayers is Professor of the Humanities and President Emeritus at the University of Richmond.

BackStory was created by Andrew Wyndham for the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

MALE SPEAKER: BackStory is distributed by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange.

View Resources

American Prophets Lesson Set

Note to teachers:

These lessons teach about a religious people, the realities of frontier life, religious prejudice, westward movement, and the complexity of settling the west. There is a wealth of material provided, enabling teachers to make choices based on the amount of class time you can devote to this story and the academic level of your students.

The group of people central to the story is officially The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Because they derive their religious tenets from The Book of Mormon, they are most commonly called Mormons. They call themselves “Saints.” In the materials provided, these three designations are used interchangeably. Also, the story is broader than the initial evacuation of Nauvoo. The Saints were a growing group, gaining converts from near and far. Migration to the Great Salt Lake Basin continued for over a decade, swelling the number of migrants and settlers detailed in parts of this lesson.

American Prophets Main

Download FileAmerican Prophets Handouts

Download FileAmerican Prophets Standards_Citations

Download FileAmerican Prophets Sources

Download File